Matthew Parris, one of many MPs who have failed to survive on benefits for even a week, has headlined in The Times today under the banner, ‘We must ask whether generous benefits for conditions such as stress have made opting out of work too attractive’. Oh give over, Matthew. The Department for Work & Pensions’s own figures show they are the ones diddling disabled people of out money allocated to them. What you trivialise as ‘stress’ includes conditions such as brain damage, profound developmental delay, and post-combat complex PTSD.

The DWP - and the government it both serves and by whom it is designed - is notorious from the top down for error, for secrecy, and for punishing disabled people though an inherently gruelling process. This nightmare is running a parallel with a gutted NHS. This is what successive Secretaries of State and Ministers have wanted. Don’t be their lap dog, Matthew. I mean, #Maaate.

The government runs a system of disability benefits in England known as the dreaded ‘PIP’, aka the mis-nomered ‘Personal Independence Payment benefit’. It’s a de-humanising shambles, including for many of the staff, let alone those reduced to the expendable role of ‘claimant’. And far from fostering independence, it forces disabled people to become dependent on a toxic and dysfunctional system that creates misery, medically systemic stress and hardship.

This in turn puts pressure on the ‘claimants’ and the NHS to provide ‘evidence’ for the DWP that no-one - neither NHS staff nor the disabled person - is fit, prepared, trained or funded to do.

In a report tucked away in the UK Guardian in July 2023, we learned that ‘Benefits claimants in UK were underpaid by record £3.3bn last year: National Audit Office criticises Department for Work and Pensions over its ‘material fraud and error’.

Top work, DWP. Especially as disabled people were among those targeted, advertently or inadvertently, for denial of payments to which they were entitled. One of the ways in which this is done is through the twin mechanism of giving out misleading information on helplines, followed by the denial of full backdating if and when a medical condition or disability worsens and a PIP review takes place that increases payments.

In the article, the DWP top brass typically tried to shunt the blame however onto the ‘claimants’.

The personal independence payment – which helps people deal with the extra living costs caused by long-term disability or ill health – is the benefit with the highest underpayment rate. However, the DWP said the increase was mostly due to “claimant error” – for example, where an individual’s medical condition worsened but they did not inform the department.

The DWP said: “We treat underpayments seriously and always look to ensure individuals receive the correct level of payment.” It added: “Claimants have a duty to report their circumstances correctly.”

That’s not quite right, though, is it, DWP?

Let’s go back to the beginning of the process. A person with medical conditions and/or a disability decides to become ‘a claimant’ and applies for PIP. They hand over many of their erstwhile rights to medical privacy to the DWP and the DWP’s private contractors. They are asked to supply not just copies of all relevant medical evidence, but also the telephone numbers and addresses of all their NHS and private medical practitioners and therapists. It’s daunting not knowing who is going to be contacted about you and your very intimate medical details, and what they will say about you.

That first application is usually a gruelling process, and involves a long, complex form, and a series of ‘descriptors’ that must be matched to the satisfaction of an assessor during a frequently over-long and complicated assessment session. This is followed by a report-writing, points-awarding, decision-making process that sometimes defies logic. Many, many claims are turned down both at this stage, as well as after ‘mandatory reconsideration’. Advice agencies hear consistently of severely disabled and bed-bound people being assessed as ‘capable of walking over 100 metres’, and ‘managing well’ in a kitchen and bathroom that they have been unable to access for over a year.

If, after the anxiety-inducing wait, an award is given, it may well be on the lower end of the scale - standard rates rather than enhanced - and only awarded for a short periods of time (1, 2 or 3 years) - even for incurable, life-limiting conditions like severe osteoarthritis or brain damage, and a sentiment I’ve heard expressed over and over again is that, ‘I just accepted the award. It was better than nothing. I was so stressed by this point I couldn’t face appealing and going to a tribunal’.

‘Are you here for the DWP Decision Makers’ training?’ ‘No mate, I’m the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions.’ (Painting: The Blind Leading The Blind, Pieter Brueghel the Elder)

Meanwhile, in many cases, the condition of the ‘claimant’ continues to deteriorate, frequently because the treatments they need are unavailable or inadequate, and their lives become more and more difficult. A year or so before their award ends -which can be as soon as a year after their first award was made - they are sent a ‘PIP Renewal’ pack. They know this could mean the end of their PIP award if they make a mis-step. The stress of it - real, debilitating stress, Matthew, if it comes of top of, say, post-combat CPTSD, is immense. Often, unbearable.

The renewal form has usually been in the post for two weeks, but the ‘claimant’ has 28 days to return it from the date on the letter 14 days prior. So in reality the ‘claimant’ usually has under two weeks to sort out their renewal claim. And this is where things get interesting.

Alongside needing some extra time for form-filling, a lot of these ‘claimants’ have been thinking about their deteriorating conditions anyway. So they ring the ‘PIP Helpline’ for advice on what to do. It takes them a shockingly long time and many attempts to get through, but they persevere, sometimes for days, as there are no online options for making contact. Eventually, they speak to a human. They may now have only 12 days left to return their PIP Renewal, but the DWP worker they speak to will only give them a two week extention. Oh well, it’s better than nothing they think, invoking the self-help mantra many people with disabilities use to survive the PIP process.

And what if the ‘claimant’ says that they need to report a ‘change of circumstances’ (deterioration) that may increase their award, and what to do?

Well, this is the bit where the DWP performs a sleight of hand.

‘Oh, put it all in the Renewal claim’, says the DWP worker.

The beleaguered ‘claimant’ follows the advice from the ‘PIP Helpline’, and does precisely this. They dutifully return the form by the cut-off date, preferably sending it by recorded delivery with as much medical evidence as they can amass in a few weeks about their current condition and how it affects their daily life and mobility.

The ‘claimant’, if lucky, and if they are in possession of a working mobile phone, receives a text saying, ‘We have received your PIP form … you only need to contact us if your circumstances change’. The ‘claimant’ knows that the ‘change of circumstances’ is detailed in the returned form, which the DWP has now confirmed it has, on a specific date. Let’s say the date is at the end of June 2022.

And then they, the ‘claimant’, waits.

And waits.

And waits.

If the claimant does ring the ‘PIP Helpline’, they are told the same as previously. And to wait.

A text message pops up three months later in October saying that, ‘We still have your PIP form and will be progressing your review as soon as we can. You may still need an assessment with a health professional. Your PIP will continue to be paid while we review your claim. You only need to contact us if your circumstances change.’

Three months later, the same text appears. Happy Hogmanay indeed. And then again in March 2023. The PIP backlog for renewals is acknowledged officially by the DWP, but people with disabilities are still caught up in the stressful turmoil.

At the end of April 2023, the ‘claimant’ then begins to receive text messages from a private contractor to the DWP about their forthcoming ‘assessment’ (either IAS or Capita). The first text says, ‘you do not need to contact us’.

If you do ring, you are told the same thing about your deteriorating condition. ‘It’ll be covered at the assessment.’ Then they might add in a chirpy voice of reassurance, ‘and don’t forget to enclose an up-to-date list of your medications’.

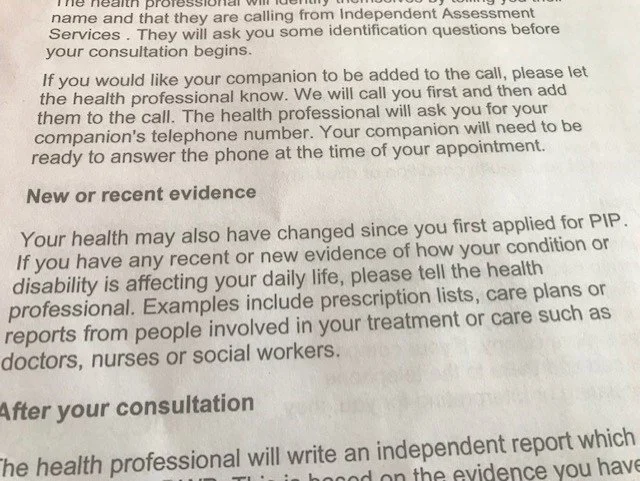

Finally, nearly a year after the PIP Renewal form and new medical evidence was returned, an assessment takes place. The confirmatory letter might appear to the unwary to support the ‘just tell the assessor about any changes’ narrative. ‘New evidence? Tell the health professional!’ It’s a continuation of the sleight of hand directed at the people who are the least able and the worst placed to detect it.

(If the DWP or IAS dispute this, they need to clarify their procedures - as of yesterday.)

The assessment can last well over the time period told to the ‘claimant’. Rather than 40 minutes or less, people find themselves trapped in difficult assessments for up to 2 - 3 hours. Then they are told there could be wait of 6-8 weeks for a result.

And so, once more, they wait.

And wait.

More texts arrive, saying that the assessor has passed their report the ‘decision maker’.

The ‘claimant’ is told not to contact the DWP unless ‘there is a change in circumstances’ but to wait for their award letters. Information about awards cannot be given over the phone. Carrying on waiting.

And then, oh happy day, the postie brings the award letter. The ‘claimant’ has had their PIP increased from ‘standard’ to ‘enhanced’ in one or both categories (daily living; and mobility).

However, and this is the crucial bit, the award is only backdated to the date the decision-maker made the decision, usually 12-14 days prior, and not to when the DWP received the renewal form and new evidence.

Oh well, thinks the ‘claimant’, I suppose it’s better than nothing, and I’m too bloody stressed to argue … I can’t go through it all again … I can’t put my family through it all again.

And so on and on it goes.

By not having their increased award backdated to the day the DWP received the information, a disabled person could, in theory, potentially lose up to £7,000, given the current back-logs and long delays, without necessarily realising it - and being too exhausted and unwell to fight it even if they do.

In a potentially more common scenario, a person who manages to have their award increased from, say, Enhanced Daily Living and Standard Mobility, whose delay from returning the form to the decision being made was nearly a year, would be looking at a loss of approximately £2,200.

What is the law here?

There have been a number of legal discussion about advantageous PIP decisions and DWP’s errors in not applying backdating.

This discussion on the advice website RightsNet.org.uk is worth reading. It goes right back to the parliamentary statute (the law) and how it ought to be interpreted. It is clear that on many occasions, the DWP is misapplying the statute to the detriment of the person with disabilities.

It’s harder to ascertain, however, how much of the DWP’s proneness to errors is part of a shadowy background policy and how much is due to incompetence.

One thing I do know - the process feels like a punishment.

‘Stress’, Matthew? You have no idea.

Acknowledgements

The DWP is a hot mess but it’s a top down hot mess. So I’d first like to say thank you to the competent and dedicated PIP assessors and DWP decision makers and managers who do get it right, and who try to make the best of a broken system. When you speak to one, you just know.

Thanks also to all those people who have shared their stories of their PIP claims and renewals; and to the Benefits & Work and RightsNet advice websites, and Disability Arts Online.

The Guardian article about DWP figures was written by Rupert Jones. The Guardian article about Matthew Parris was written by Jon Henley.

Matthew Parris was today writing in The Times. It’s pay-walled but maybe try an online archive drop website to look for it if you feel the urge.