What Did Julius Caesar Say, and Why Is It a Problem?

“Groups of ten or twelve men have wives together in common and particularly brothers along with brothers, and fathers with sons; but the children born of the unions are reckoned to belong to the particular house to which the maiden was first conducted.”

It's been a while since anyone took much notice of Julius Caesar's writings on ancient Britain as any kind of credible social commentary. There's not only the problem that he was writing for a particular audience and in a particular style - there's also the issue that so little of what he says about Britain matches the archaeological evidence.

But that's not to say that his words aren't worth looking at. His statements about (at least some) British marriages tantalise us with their allusions not just to polygamous unions but to a rare form of this known as 'polyandry' - the marriage of a woman to more than one man - as well as to how the children of these marriages were made legitimate.

The Loeb translation above seems fairly secure, by the way. For Latinists, here's the original passage from Caesar's account of his Gallic Wars:

“Uxores habent deni duodenique inter se communes et maxime fratres cum fratribus parentesque cum liberis; sed qui sunt ex his nati, eorum habentur liberi, quo primum virgo quaeque deducta est ”

There are other translations of course - and I think most Latinists would have their preferred nuance - but they all pan out pretty much the same from the 19th century onwards.

“Ten and even twelve have wives common to them, and particularly brothers among brothers, and parents among their children; but if there be any issue by these wives, they are reputed to be the children of those by whom respectively each was first espoused when a virgin.”

Is the Idea of Polyandry Useful for Studying Iron Age and Roman Britain?

When I was writing my PhD thesis on Roman villas in Britain, and looking at evidence for social structure and patterns of inheritance in late pre-Roman Iron Age ('LPRIA') Britain, this particular passage of Julius Caesar's fascinated me. But I found it really quite difficult to know what to make of it, especially given the lack of discussion of it in the standard books on Late Iron Age and Roman Britain. When their authors talked about 'complexity' they would focus on big landscapes, visible settlements and earthworks, trade, migrations and craft specialisations. There was little room for the family from a female perspective. And such discussions that do exist about Caesar's remarks on polyandrous marriage tend towards describing it as being a 'primitive' practice - but I'm not so sure that's where the evidence in fact points.

I had questions without answers. Did Julius Caesar really observe polyandry? If so, was it widespread and common, or a rare form of class-based inheritance protection?

I had a look at the other known examples around the world, and how polyandry functioned alongside property codes and inheritance rules. The first thing that stood out to me back then was that polyandry was believed to be rare. Very rare. And much more so than polygyny (the marriage of woman man to more than one wife).

Polyandry and Ethnography

The sources I relied on especially were Murdock, and Ember & Ember. Murdock's World Ethnographic Sample revealed only four societies - less than 1% of the total in that study - where polyandry could be documented. These involve some Tibetan communities and the Toda of India. It's interesting that as with Caesar's 'example', the Murdock cases are also those of fraternal polyandry, and also involve the concept of social fatherhood as well as biological paternity. Spatially, polyandrous marriage arrangements can include separate rooms for different adults within the same house, and clear rules of inheritance.

But this is far from a simple narrative.

Polyandry is never practised universally throughout a society. This would entail an enormous surplus of males over females that even female infanticide (if it even existed - and it is frequently invoked in historical studies as a 'explanation' without data) could not consistently maintain.

Also, is it (was it?) really as rare as Murdock and his (male) contempories said? There have been challenges to Murdock's conclusions in recent years, eg by anthropologist Katherine Starkweather, who noted that 'informal polyandry' made sense especially in societies where control of resources and multiple parenting would be beneficial.

But Starkweather isn't being particularly radical. Ethnographers in the 1930s did frequently apply the term 'polyandry' to sporadic instances of the association of one woman with more than one men in contraventions of cultural norms, or to case where women were permitted sexual relationships with the brothers of her husband although she was not in a direct economic and residential relationship with them. In fact, Murdock found that these kinds of sexual entitlements were not particularly rare, unlike actual polyandrous marriage.

So Is It All About Sex?

So did Caesar simply misunderstand a situation where women in Britain had greater sexual freedoms than women (ostensibly) had in Rome, and confuse that situation with marriage?

His concern with what we might term the 'social paternity' of any children of these supposed marriages might indicate either 'true' polyandry or socially acceptable plural sexual relations.

Boudicca in her Prom dress

Caesar was learning about a society quite strange to him personally - a society and a place where just over 90 years later there would be three Client Kingdoms, two of which (after the death of Prasutagus) would be led by women, Boudicca and Cartimandua. Some women could lead and some women could inherit land. Some women could hold power and some women could make history. Is it such a far stretch to think that some some other women might have had sexual freedoms within the protection of social tolerance and legitimacy codes?

But then that leads down a whole other path of exploring preconceptions about power, autonomy, consent and desire. And that's another piece of writing.

Are there then other passages in the historical record that could be relevant to this immediate discussion? There's an (admittedly much later) passage in the Epitomes of Dio Cassius which is often held up as a comment on the sexual freedoms of British women:

“... a very witty remark is reported to have been made by the wife of Argentocoxus, a Caledonian, to Julia Augusta. When the empress was jesting with her, after the treaty, about the free intercourse of her sex with men in Britain, she replied: ‘We fulfill the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest.’ Such was the retort of the British woman.”

This is a difficult passage to interpret once taken out of its elite context (aren't they all ...) but if we do take it at face value it appears to be a vignette about a well-to-do British woman telling an empress - according to Dio - not to view her and her female British compatriots through the lens of Roman hypocrisy. She seems to be acknowledging difference, and hinting at an open code of behaviour rather than 'open secrets'. However, and unfortunately, that doesn't take us very much further forward.

And So ...

Because the known anthropologically documented instances of polyandry are so rare, it's difficult and probably unwise to try to paint any big pictures about causes, such as shortages of woman to marry. After all, one would have to try and explain such shortages in the first place. It's only really possible to speculate about outcomes - and the one that seems a 'best fit' in the circumstances seems to be a concern about the passing on of land and assets to a future generation, and a minimising of 'splitting' of estates.

If such a set-up did exist in 'LPRIA' Britain, perhaps the intention was a very tight control over legitimacy and inheritance by those families who practised such unions. Is it even remotely visible in the archaeological record? Is it even worth looking for, for example among the landowning class in the countryside of Roman Britain?

Sparsholt Roman villa, Hampshire

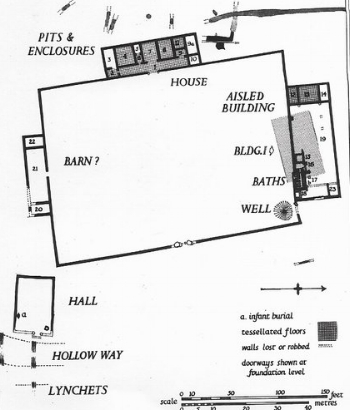

Well yes and no. There certainly are British peculiarities in the quasi-elite rural archaeological record of Roman villas in the province that aren't seen on the continent, such as the layout and growth of the villa sites from the first century through to the fourth century. There have been many attempts to explain these peculiarities, from J T Smith's 'Unit Theory' to my own examinations of aisled farmhouses and the multiple villa buildings which were built on the same sites.

Is it driving the evidence too hard to push it back towards a possible link with Caesar's observation? After all, he got it wrong about the British inlanders' diet, agriculture and clothing, and so much else beside. So, yes; I suppose it a distance too far. But I nevertheless remain tantalised. Polyandry in the 'LPRIA' would have been far from a primitive 'throwback' practice, but rather could be the socially constructed custom of a wannabe-elite that were already becoming removed from the primary means of production - or were at least desirous of emulating the elite that were; and they would have been conscious of preserving such resources as they had in order to try to achieve that.

Maybe.

Acknowledgments

Loeb Classical Library; www.forumromanum.org; the Latin reading blog; my PhD thesis, Aspects of the Roman Villa as a Form of British Settlement (Newcastle University Library, 1988); George Murdock 1957 (and later editions) World Ethnographic Sample; C R Ember & M Ember 1977 (and later editions) Anthropology; https://www.unl.edu/rhames/Starkweather-Hames-Polyandry-published.pdf; Lindsay Allason-Jones 1989 Women in Roman Britain pp 33-34; J T Smith 1978 'Villas as a key to social structure' in M Todd (ed) Studies in the Romano-British Villa; and the wonderful Ladybird Books (re: images).