In the 1930s, three intriguing burials were found by Adrian Oswald and his workforce in the upper archaeological levels at Norton Disney Roman villa. Some might call these inhumations strange, lying as they did not in a burial ground but on top of or aligned with dismantled walls of once-imposing buildings from the Roman era. Why are they there? How rare are such burials? What can they tell us about life and death and the end of Roman villas in Britain - and indeed the end of Roman Britain itself?

Since I wrote my previous blog piece on the development threat to Norton Disney Roman villa, I’ve come across some more moth-eaten draft fragments of my PhD thesis and a box file of old notes. It started me thinking all over again about the segueing (or not) of the ‘end’ Roman Britain into the early Medieval era (aka the ‘dark ages’ or ‘Saxon period’), viewed through the lens of the archaeology of these villa farms.

Late burial at Ilchester Mead (Hayward 1982)

To me, the earliest villas show the new Roman economy ‘writ large’ on the British landscape in the first years of the imperial occupation of Britain. The same villa sites also go on to reveal rapid changes to the visible material culture at the end of Roman Britain - approximately very late 4th century to early 5th AD - with the later phases reflecting some pretty startling dislocations of the economy and culture of these places. The 'Romanised' economy of Britain broke down for a number of reasons. Inflation, lack of subsidised sea-borne supplies of goods to the depleting legions, the associated collapse of the pottery industries, the demise of mosaic workshops, social and political upheavals, and religious changes and revivals, are all implicated. But the jury is still out on definitive solutions to these problems - and sites like Norton Disney remain key to our future understanding of these major archaeological and historical problems.

What we do know is that where preservation is good, aspects of ‘continuity’ of occupation or cultural use of these large farming sites can be viewed archaeologically at villa sites in Britain across an extraordinary sweep of time. Many villas show continuous occupation from at least the late Iron Age into early Roman - and Norton Disney is now known to be part of that important group - and where conditions are right, the same can be seen at the other end of the Roman period.

Villas were ‘performance houses’ as much as they were working farms, in a new world of money, taxation, and hard financial rather than predominantly social obligations. New villas mirrored and maintained a new type of cultural and economic activity across a British landscape that was absorbed into the Roman world in a unique way. And when 'villa-ness' dropped away quite rapidly in the twilight years of Roman Britain, there were still expressions on these sites of people making the choice to use the villas, although in different ways. There were, at sites like Norton Disney, whispers of the old and the new right up to the end through strange burials and other deliberate, curious deposits.

Late or 'Secondary' Burials

Skeletons on mosaic at Southwell, Notts (Daniels 1966)

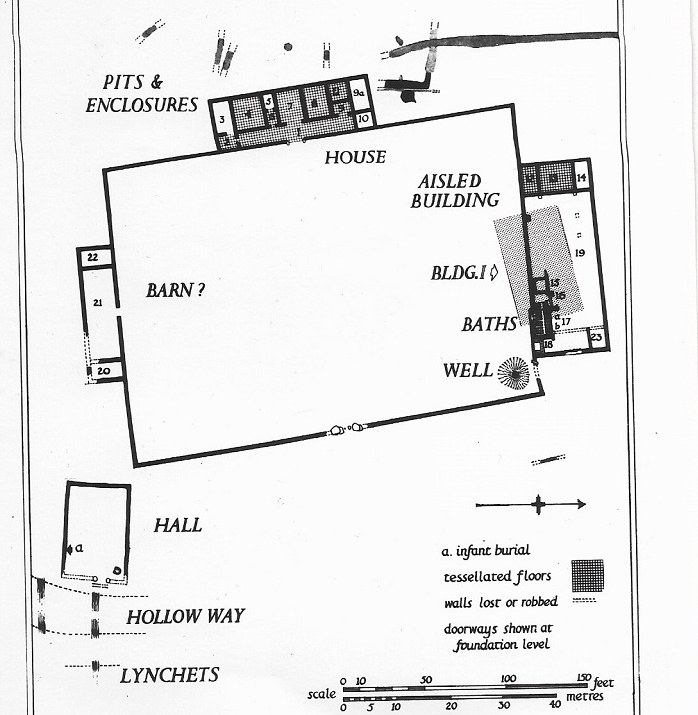

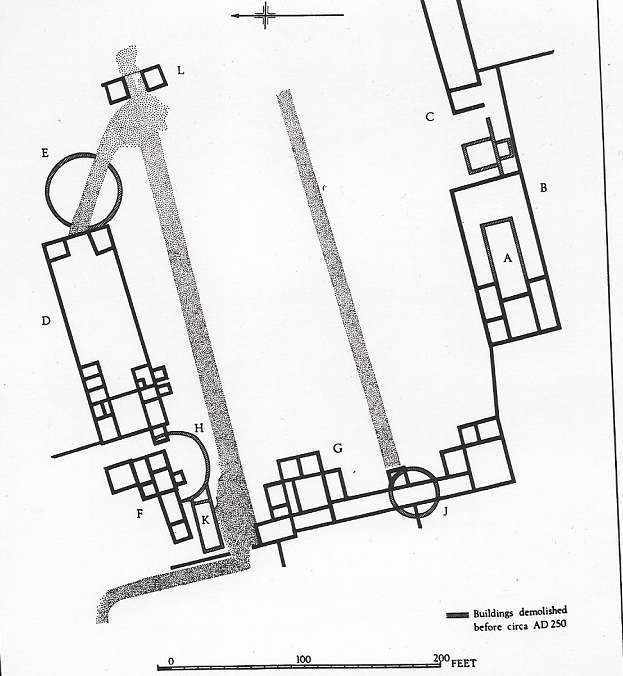

‘Secondary’ burials – burials on top of features that weren’t designed originally to have a mortuary or funerary function – were carried out on a number of known villas throughout the province of Britannia, such as Llantwit Major in Glamorgan, Southwell in Notts, Rockbourne in Hants, Winterton in Humberside, Ilchester Mead in Somerset, and Denton and Norton Disney in Lincs. Frequently there are associations and alignments with parts of the previous villa - wall foundations, mosaic or tessellated floors - and a notable correlation with the presence of aisled farmhouses (see below).

But why? What’s going in here with the archaeology, and what could it mean? Is the emergence of early Christianity involved - the villa remains perhaps being thought of as relic churches or other relic buildings of a previous age? And how important is Norton Disney as a piece of the jigsaw in the developing picture?

The Llantwit Major 'Explanation' - and Other Ripping Yarns

John Storrie excavated at Llantwit Major Roman villa in 1888. For a time context, think Jack the Ripper and Three Men in a Boat. I don't think Storrie was exactly enamored of his craft, noting at one point in his log that 'one day's digging [is] very much like another'. But there were some discoveries that allowed him to tell a most wonderful tale - a tale that, with a little variation, was to be repackaged by other villa excavators down through the generations.

In brief, Storrie found in Room 2 what he determined to be the remains of 38 males, one female and two children. The excavation party also found the complete skeletons of three horses which 'were all found within the walls of the room with the tessellated floor; one was found lying over the skeleton of a man'. Room 2 had a tessellated floor, and was bipartite with the two 'chambers' divided by a line of arch stones.

To cut a long story short, the narrative that Storrie created was that because some of the burials were face down, and given the presence of the human and equine skeletons, he fancied that he could see horse-hoof impressions in the tessellated pavements. His conclusion was that the people and the horses had been slain where they lay, the horses kicking up the pavements as they were killed. The absence of weapons and objects of any kind he attributed to looting.

This kind of event specific 'explanation' occurs time and time again in discussion of Roman villas, even up to our current generation, often with reference to the so-called Picts' War (or 'Barbarian Conspiracy') of AD 367 - and this despite no other evidence, and despite a more discernible pattern of human and animal burials on top of out-of-use villa floors and wall foundations as though part of what Ralph Merrifield called 'rituals of termination'. I remember when 'Time Team' were digging up bits of Turkdean Roman villa, and sitting down briefly with the producer in a caravan behind the scenes, trying to convince him that the horse's head sealing down the end of a villa room's use-life was really, actually much more interesting than chasing mosaics ...

At Rockbourne villa, despite on the one hand arguing for one (footless) skeleton being evidence of an execution and burial, the excavator Morley Hewitt also fancied the idea of squatters. On the floor of Room XIV the skeleton of a 'middle-aged man', crouched, and with a broken back, was somewhat ingeniously interpreted as evidence that, 'he was probably robbing the roof of tiles and fell through or was sheltering in a dilapidated building. He was lying on some tiles and there were also tiles above him.'

And therein lies the other frequently-favoured 'explanation' for late burials on Roman villa sites - implausible walls falling implausibly onto footless bodies.

The 'Aisled Farmhouse' Connection

I coined the term 'aisled farmhouse' for my PhD thesis in order the describe those villa buildings commonly seen in Roman Britain comprising large basilican working farmhouses with Roman-style material culture. They are peculiarly British in style, size and function. Although aisled wooden barns are of course known on the continent, the particular association of aisled farmhouse and villa house in Britain is an arrangement not seen in other provinces.

At some sites the aisles were marked by posts (which survive archaeologically as large post-holes or post-pads); and often these were connected by walls to form rooms, including, on occasion, small bath-suites. In the sub-Roman period or later it is possible that these buildings in particular might have held some appeal as 'church like' in an era where early Christianity was establishing itself amidst the Pelagian and pagan competition in the countryside.

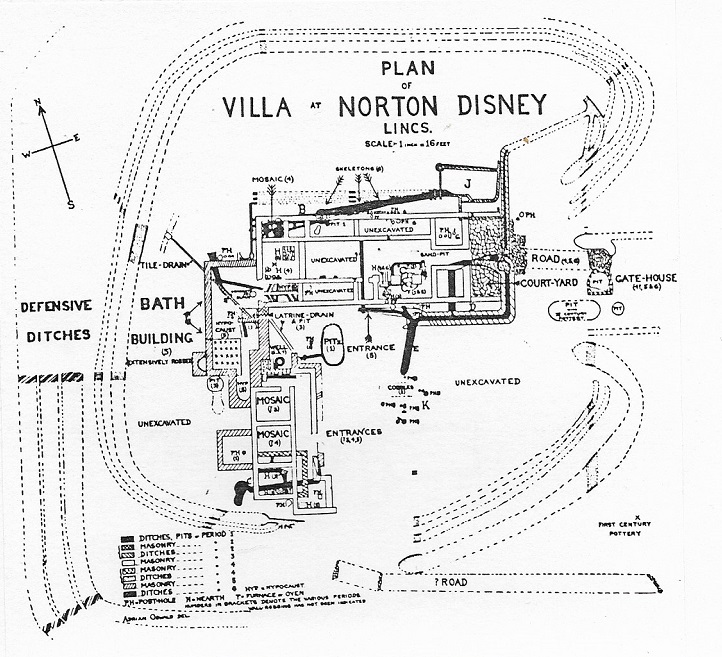

The arrangement at Norton Disney was the classic British one, with a developed 'Romanised' aisled farmhouse at right-angles to the (smaller) corridor 'show house'. And, as at other sites, it is in association with the aisled farmhouse that the burials were found.

Norton Disney - the Evidence

Three adult inhumations were found at Norton Disney. Two of the skeletons lay just to the north of, and aligned with, the north wall of the aisled farmhouse; and the third skeleton lay on top of the surviving foundations of this building. The three skeletons approximate to a west-east orientation, for this building runs roughly west-east.

Two of the skeletons were possibly male, and the other female, according to the excavator Adrian Oswald and Buxton his bone specialist.

One of the skeletons was covered by wall stones; at least one was without feet.

It's also worth noting that Oswald claimed seven fires in the history of the site, but the available photographs don't show fire marks or charcoal anywhere underneath or in the vicinity of these bones.

The Excavator's Story

Despite the fact that in his specialist bone report, Buxton did not observe any visible signs of violence to the bodies, the excavator - like Storrie at Llantwit Major - was keen to offer an event-specific 'explanation' for the inhumations.

These skeletons might perhaps have passed as burials were it not for the position of no. 1 on the wall ... How did the skeleton on the wall come there? The adjoining rooms and all the levels of this period bore traces of a fierce fire ... It is perhaps permissible to suggest that these people were trying to escape from the burning building and that as the man on the wall passed over the threshold of the door the lintel collapsed on him, crushing the body into the distorted condition in which it was found ... [the body was crouched on its side] ... It is also possible that the other two people met their death in a collapse of the outer wall; certainly the skeleton of 2 was covered by wall stones, and at this point the foundation of the wall had subsided sideways in a northerly direction ...”

Oswald's photographs actually show quite ordinary extended inhumations, one with one arm crossed over the pelvis, reminiscent of at least one found at Winterton villa. The missing feet are similar to late burials known from other villa sites, eg Southwell.

... “Human remains were found elsewhere on floor levels of this period ... these finds amounted to ten in number. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the end of the occupation was a violent one, and that it took place in the troublous times which the country endured in the mid-fourth century. It is curious that the site was never reoccupied ...”

Oswald’s rather fanciful interpretation was queried by Graham Webster in 1969 who wrote that the published photograph of the skeleton on the wall 'does not support the theory, as it does not show the smooth threshold stone below the skeleton' which shows no trace of fire damage. He added that it is in any case structurally impossible for a wall to collapse so opportunistically as in the manner envisaged by Oswald.

In a way, though, Webster’s preferred explanation - 'the absence of restraint in the more barbarous days' when 'the occupants are interring their relatives nearer at hand, in the ruins of the old house' - is itself a bit odd, involving some sort of bizarre apathy or lethargy on the part of the bereaved concerning the burial of the dead, rather than deliberate choices being made about preparation of the bodies and re-use of these particular sites.

The 'Gallic Parallels'

There is a 'triple coincidence', to use the phrase of archaeologists Morris and Roxan in 1980, of villa, cemetery and church known from across the channel in Gaul. These recurrent associations show a clear continuity in the Gallic contexts - there's no time gap, and they segue nicely. However, where the same 'triple coincidence' is seen or suspected at villa sites in Britain, eg at Meonstoke in Hants or Empingham in Leics, the picture is much less clear and is not yet fully understood, because the churches and cemeteries appear to be properly established some centuries after the villa buildings went out of use.

Are the burials we've looked at above the conceptual 'missing link' between villas and later cemeteries, churches, and indeed parish centres? Some villas have churches close by with Roman building materials, possibly from the villas themselves, built into the fabric; some villas have later burials on the sites; some villas appear to be at parish centres or on parish boundaries.

There are parallels from Gaul for the placing of reused building material over and around secondary villa burials. Indeed, there is other evidence from Britain for building material such as tiles and slates being used in ritual acts, including at villas - down wells and in votive pits, for example.

It looks as if we could be seeing a sequence of villa demise and dismantling - what some might call 'robbing' - followed by secondary burials which respect the existence of the ruined building certainly in physical terms. But respecting visible remains also in conceptual terms? That's a leap, certainly - but worth researching.

And so ...

Villas were places of the living and places of the dead. Sometimes, at their own ends-of-life, the buildings may have become places of the ‘outside dead’. The sites appear to have been out of use as the villas they once were, with bodies being lain on wall foundations indicating that much of the building stone was long gone for other purposes. Some bodies were covered with some of the remaining, un-robbed building materials - stone and tiles mostly. Some were laid on already dis-used tessellated floors.

They were both post-villa and part of the villa.

The whole narrative should not be about barbarian attacks and single-episode Hollywood explanations - it should be about villa sites at the end of Roman Britain being adopted or otherwise used as places of memory. The memories were reconstructed and reinvented, certainly - but memories of the past, and symbols of the present and the possible future, they nevertheless were.

Whether the burials on these sites and the actions around them were remembrances or desecrations of pagan, Pelagian or Christian rites, they suggest these villa sites were still visible and remembered in some way, whether it be from earthworks, material scatters on the ground, literal memory or place-names - in some ways, much as they are known today, but through different lenses.

Villa sites like Norton Disney matter, as part of our irreplaceable heritage and as part of our future researches. Making the active decision not to destroy them is to be on the right side of history.

References: Oswald A 1937 'A fortified villa at Norton Disney, Lincs' in Antiquaries Journal (including L H D Buxton's bone report); Hayward L C 1982 Ilchester Mead Roman Villa; Daniels C M 1966 'Excavations on the site of the Roman villa at Southwell' in Transactions of the Thoroton Society, Notts 70; Storrie J 1908 'Report on Excavations near Llantwit Major' in Trans Cardiff Naturalists' Society 20; Morley Hewitt A T 1971 Roman Villa. West Park, Rockbourne; Webster G 1969 'The Future of Villa Studies' in Rivet A L F The Roman Villa in Britain; ; Stead I M 1976 Excavations at Winterton Roman Villa and Other Sites in North Lincs; Johnston D E 1972 The Sparsholt Roman Villa; Morris R and Roxan J 1980 'Churches on Roman Buildings' in Rodwell W Temples, Churches and Religion in Roman Britain

See also, blogwise: Scott E - see here and here; blogs by Richard Parker and Antony Lee. Go to the main menu at the top of the page to see my other stuff here on Roman villas and Roman Britain.