“That same night, the screaming started, as giant cockroaches flew into the communal awning and landed on people’s backs and heads”

Yesterday a fascinating and important Twitter discussion took place about excavations, initiated by Penelope Foreman, and how tough they can be for students and other participants.

Dr Anne Teather tweeted: 'Too often it's "digging is fun" when actually it can be isolating, physically difficult, socially challenging. No sense of autonomy and it can be v gruelling.' Dr Matt Pope agreed, and added that 'we have to be upfront that this will be tough at times'. Should students disclose beforehand to excavation directors that they have issues? Cath Poucher told a salutory tale: 'Sometimes I don't [disclose] due to fear of reaction & stigma / not being treated the same as others. Which happened on every dig I went to & disclosed my disability. So I stopped disclosing.'

This post was the precursor to the Dig Food Blog series

1 Excavation Challenges - Food, Fieldwork and Difference

2 Please Feed the Archaeologists (Recipes 4 All)

4 Dig Food: It's Vegan and Gluten-free and Type2-friendly - prep and stores

5 A week of fieldwork recipes - vegan, gluten-free and Type2-friendly

Photo Credit: the legendary Bob Muckle, Canada

Reading yesterday's Twitter discussion between experienced archaeologists about the toughness of excavation, especially for those with a physical disability, health problem or a mental health issue, it struck me that my experience of training excavations has been very mixed, for lots of reasons. It's certainly not the case that excavation in pre-health-and-safety days was somehow more fun. I had my share of, shall we say, less than optimal digging experiences 'back in the day'.

I think that we still have problems in these areas, and that we also have a major issue to address regarding non-neurotypical students with sensory processing issues like Asperger's / ASD. All these factors need an honest airing so that we can properly identify them, and openly discuss the degree to which the excavation environment (cultural and physical) can and cannot be shaped to accommodate different needs.

This discussion really resonates with me, as I recall my 'digging past', and face the fact that I won't be mattocking a section through any Iron Age earthworks ever again. How does it feel for people who face physical, mental and sensory challenges, as well as the challenge of whether or not to disclose? One thing it's not, and never has been, is fair. So what have we learned in the past generation, and how do we change it?

1. The Horror of the 'Training Excavation'

Two of my least favourite archaeological experiences have been: ending up in hospital whilst on a training dig; and, many years later, marking students' performance and participation on excavation modules. What do you do, for example, when a student's behaviour is inexplicable, such as refusing to drink water on a searingly hot day, or just not wanting to dig? Is this a disciplinary matter or a behavioural issue? How does one mark (grade) this kind of (non)participation when it's gone on all week, and you suspect there's more at play than some kind of defiance? And how do you grade a student who's landed up in hospital with an injury like a foot fracture because they went arse-over-tit down the side of a hillfort?

The Cheviots, Northumberland

Looking back on my own university degree experience, I was part of the generation who were expected to 'just get on with it'. You fitted in, or you bailed out. The compulsory excavation element in Year 1 (for me, 1979, the year of London Calling by The Clash) was an end-of-academic-year dig in July. The entire dig team comprised one lecturer and 10 single honours students. I'd excavated before, but we were all pretty green, and it just wasn't enjoyable. Over two long weeks we opened up and skimmed off part of the top of the scant remains of a faint prehistoric presence on the summit of one of the Cheviot Hills in Northumberland. Accommodation involved students sharing twin rooms in various catered B&Bs in Wooler, and there were no toilet facilities by day on site.

It would have been difficult if not impossible for anyone with a physical disability to manage on this dig, because they probably couldn't have got to the site by day or negotiated the steps and bathrooms of the B&B by night. After the 20 minute drive in a landrover to the hill that the site was on, it was then a further 20-30 minute hike up the very steep slope from where we left the vehicle, carrying digging equipment and the day's rations-per-person up and down each day. There was one immersion tank of hot water per B&B per evening, so we each had a desultory, lukewarm bath; and it was difficult to socialise during what was left of the evening as we were broken up into different B&Bs, and most of us had little money left at the end of the year to go to pubs. For me at least (I had some mental health and other health stuff going on already), it was a pretty grim and depressing two weeks. I probably demonstrated little enthusiasm, but completed the element and went through to Year 2.

Housesteads Roman fort

The compulsory Year 2 excavation element in 1980 was a wholly different experience. We joined the team at an established dig at Housesteads Roman fort on Hadrian's Wall, along with diggers from a number of universities, all staying in a historic Hall of Residence at Leazes in the centre of Newcastle. Charles Daniels the main lecturer / director lived locally but spent quite a lot of time with us socialising, and we mostly had our own bedrooms. There were proper baths and showers in Leazes, and 'porta-loos' on site. The mini-bus transport took us to within a short, easy walk of the fort. Most of the supervisors were 3rd year archaeology students from Newcastle and they went out of their way to be friendly and helpful. I felt much more comfortable on this larger dig, where it was possible to become inconspicuous. I could take my lunch and eat it sitting on the edge of Hadrian's wall looking north up into Northumberland, and be left alone; or I could sit in the site hut with others and make up jokes about Charles.

All students on both training excavations, without exception, were expected to dig. To literally, physically, dig, with trowels, mattocks, spades, shovels, buckets and wheelbarrows. Day to day, this could be very physically tiring, and if you were put on your own in a trench (a 'reward' for being capable of working without the need for supervision) it could feel quite lonely and isolated and boring. But dig we did. The recording work and the small finds processing was the province of the supervisors and the director(s). I was physically strong back in those days and (a whole other blog piece) was very much 'one of the lads' with a fear of being perceived as feeble. We looked forward to getting back to Leazes every day and having dinner (dished out by cooks and eaten informally) and socialising either in the common rooms or, when money allowed, at local pubs like the legendary Trent House. The established dig worked much, much better for students than the ad hoc one the year before.

2. And if ASD Means You Don't Like Dirt?

How would a student who had, say, ASD have coped on those excavations? I doubt they would have found them 'fun'. It is a very moot point for me, because I support and tutor students with ASD and I've been involved in their preparation for work placements and their survival of all the new sensory and organisational experiences that come with it. I have one tutee who loves learning about the past and is intrigued by what lies beneath the soil - but he has sensory issues with dirt; with crowds; with having to share bedrooms and bathrooms; with being under-monitored; with being over-monitored; with food; and with wearing certain clothes. You can't just drop him into a new situation. But what does work, is carefully trialling new things, and short but patient bursts of pedagogy, followed by leaving him to explore this new knowledge on his own, especially if it involves a piece of equipment or tech.

What would work on a dig would be allowing this student to participate more in the recording of features and finds. This really should be best practice anyway, necessitating as it does careful observation of the digging and uncovering processes and identification of contexts, as well as teaching the essential skills of recording. Would my tutee ever be able to achieve the professional standard required to work as a circuit digger in the ruthlessly efficient world of contract archaeology? No, probably not. Could he ever achieve the professional standard required to participate on a dig as a specialist, or assistant specialist, in a related area of excavation, such as surveyor, pottery draughtsperson or photographer? Yes, I think so, as long as the supervisors were prepared to initiate pedagogy in these areas at an early stage and relinquish some of their hold over what are often perceived as supervisor-level tasks - which, as the Twitter discussants pointed out, would need to be director-led initiatives and outcomes.

3. Are Students Always Safe? Getting Really Ill on a Dig in the Middle of the Desert

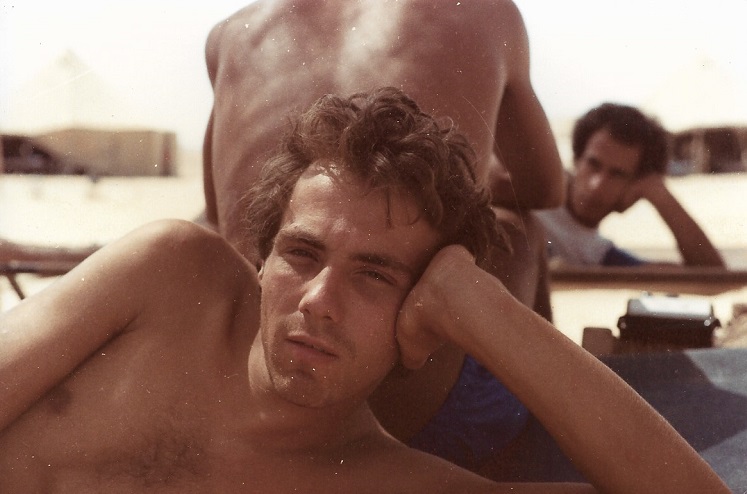

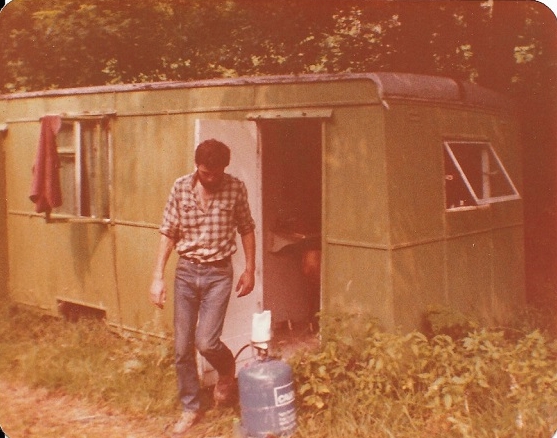

Greg (from Australia) at Shiqmim 1984

In 1984 an Israeli archaeologist came to Newcastle University and gave a talk on his excavations in Israel at the chalcolithic site of Shiqmim in the Negev Desert. He said the training dig that September was open to student volunteers from Newcastle for 'free' - we'd just have to pay for our own flights. I was in the second year of my PhD on Roman villas, so the site didn't have any direct relevance to my doctoral research. However I decided to go on the dig because I wanted excavation experience in the Middle East; and I could tie it together with a visit to the Dead Sea to try to find a way of dealing with my worsening psoriasis.

So off to Israel I went, and at Shiqmim encountered diggers from all over the world. We met as instructed, most of us strangers to each other, at the bus station at Be'er Sheva one hot day at the beginning of September, and we were driven through the barren rocky landscape, seemingly without landmarks, towards the site in the heart of the southern Negev. On that drive we were aware that it was getting even hotter. And drier. I'd already spent a month at the Dead Sea, with a few days' break at Eilat in between, and was relatively acclimatised to a 40 degree heat - indeed I was looking like an advert for bronzed health, and knew to drink my five litres of water a day - but this was grim. The relentless heat at Shiqmim enfolded us day and night, until just before the dawn when the temperature plunged and it suddenly became too cold to be of any relief.

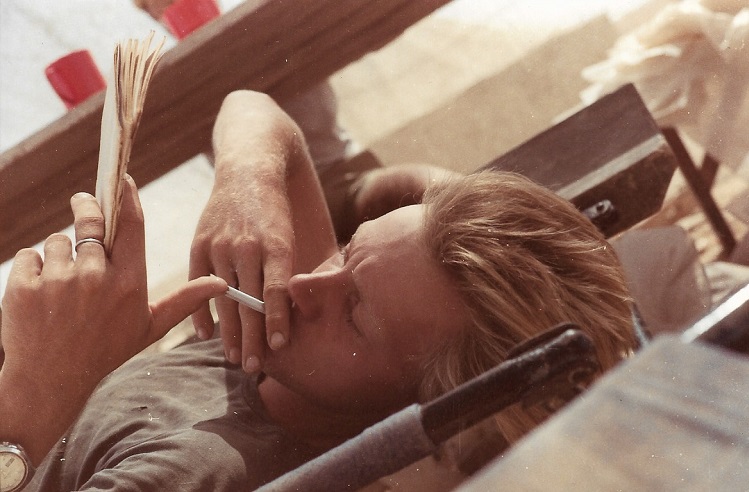

From the start it was like a horror film, with the diggers being picked off one by one. On the second day, a young German woman was heard sobbing, and in the pale pink dawn light was driven back to Be'er Sheva in a state of considerable distress by one of the dig's Bedouin workers, her face eaten alive by mosquitos. That same night, the screaming started, as giant cockroaches flew into the communal awning and landed on people's backs and heads. I wasn't too bothered by that, or the scorpions, but plenty of people were. The heat was stifling, and the long afternoons where no work was possible were hard to fill. We lay on camp beds and smoked, talked, and shared the few available trashy paperback books by one person reading a page, tearing it out and passing it on to the person lying next to them, and so forth and so on.

We shared ex-army eight-person tents, which were mixed sex and lacked privacy. This sometimes meant couples doing Couply Things at night, which felt a bit awkward for those trying to sleep next to them. The food was very basic and the cooking pans were washed in cold water. The latrines were holes in the ground, with a bag of lime to the side to shovel on top of the shit, There was a canvas open-topped tent with a trickle of water coming out of a tank that was the camp shower.

I noticed here, as I had at previous digs, that the students and the volunteers did all of the actual digging but virtually none of the site recording or small finds work. Those tasks were reserved for the supervisors and the director's assistants, who seemed to be very mindful of their status. I didn't even get a day's break on food prep and pan washing, because I was 'good at digging'. So digging's what I did.

Diggers watch as Director, Director's Assistant and Supervisor record their work

A few people started to get ill at Shiqmim. Not everyone did - it was luck of the draw - but it was bloody awful if you were one of the ones who did. I was due to be there for the whole duration of the dig - five weeks I think it was - and thought I was doing fine. And then, near the end, I succumbed to the dreaded Shiqmim Shits. I also had infected mosquito bites on my legs. Despite the best efforts of fellow diggers to look after me, I developed a fever, couldn't leave my camp bed, and in the end wasn't able to keep down any water. It was scary and disorientating, and by the time I was deposited (alone) at Be'er Sheva Hospital I had - according the the Emergency Room doctor - not terribly long left to live. I was put on a saline drip for a couple of days and was then collected and taken back to the dig, where I waited to be taken back to Be'er Sheva again once Yom Kippur had ended, and took the bus to Tel Aviv. I made it home to the UK, wanting to kiss the tarmac at Heathrow, a few days later. 'How was your health holiday?' my dad asked.

My getting sick meant I wasn't invited back the following year to supervise even a small section of the site. I can understand the logic of this, but it still stung a bit because I hadn't wanted to dice with death. I had found the events pretty appalling.

That was not a good digging experience.

4. Getting it Right at Castell Henllys in Rural Wales

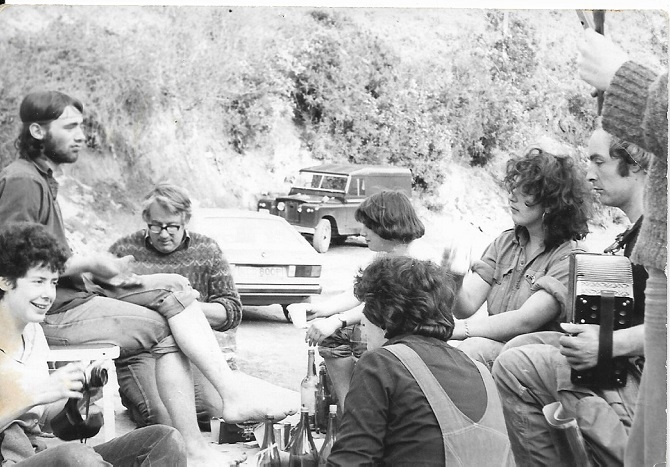

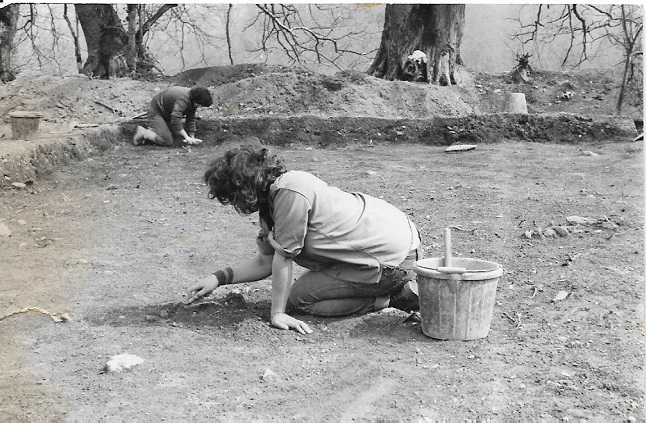

Playing cards in front of the farmhouse at Castell Henllys, Easter 1981. Director Harold far left; Supervisor Lisa far right.

Prior to Shiqmim, I'd been lured into a false sense of security about being on fairly remote digs by Harold Mytum. Harold's long-term excavation at Castell Henllys in Pembrokeshire (Wales) was, as far as dig culture, learning and acommodation were concerned, one of the most successful digs I've been on. The dig combined an element of communal living with the ability for people to have their own sleeping or 'chill out' space (where they could also eat privately if they chose) which, perhaps by accident more than design, turned out to be an model of how a dig can 'work' for everyone involved.

The director Harold opened the site up over the Easter vacation in 1981, and resumed the excavations in the summer. There were rooms in the farmhouse, a couple of old caravans of considerable antiquity, and plenty of room for tents. As the digging seasons continued on this site over the years, some extra 'dorm' type huts were built, but there was always a good campsite space for people who wanted the privacy of their own tent, communal living for those that wanted that, and decent toilets and showers with private cubicles. The site had two access routes - either straight up the slope, or via a gentle, curving path to the rear of the site which was manageable for most ambulatory people and accessible to vehicles. If anyone hurt themselves or became ill, Harold cheerfully took them to the local health centre and let them rest up.

Harold and Lisa - hardly ever a dull moment at Henllys. Easter 1981

And just as importantly - I found Harold and his lead supervisor Lisa to be immensely egalitarian. They didn't 'reserve' tasks for themselves. If you dug it, you got to record it, and if you didn't know how to, Lisa would show you. If you wanted to help build a flotation machine, or draw pottery, then that's what you did. They taught us all so much, and although I was still doing a lot of hard, physical work, I was also having days where I was sitting, quietly, either on my own or with another digger, developing an archaeological skill which would benefit the site.

Harold also 'got it' that digs can be pretty boring in the evening if you're based in a rural setting, and that diggers are skint, so he provided the kit for home brewing. This was inspired thinking. And once we had Harold trained up to accept vegetarianism as a valid eating option, he was pretty damn perfect.

That first Easter season, we were a quite a ragged crew but it was such a happy, productive place. I'd just got out of a long stint in hospital and had had to take that year out of university (psoriasis again). The farmhouse at Castell Henllys was a welcoming place to be, with its raw beer fermenting in the big slate fireplace, the ever-present aroma of boiled spuds and macaroni cheese, and talk of reconstructing an Iron Age roundhouse in the summer. The test of it for me, looking back, was the arrival a very shy young woman who'd never dug before. She was clearly anxious, but because the dig culture was kind she was content. She taught me how to do the Daily Telegraph cryptic crossword whilst I taught her how to play ribald card games. We became friends, and we both got a massive amount out of that dig and the people on it.

That was a really good digging experience.

And so ...

I definitely agree that the rigors of excavation should be made clear, and that different fieldwork options should be available for students who feel they cannot take part in a particular dig, or in a particular activity on a dig. Module marking (grading) of students on excavations also would benefit from more thought about the judgements that go into assessing concepts like 'effort and attendance', 'engagement with learning', and 'overall performance', when the whole fortnight's been a macho-fest of six foot high barrow-runs and senior-level possessiveness over the new surveying equipment. Maybe the reason that that student told you to fuck off was because she was feeling like shit, it was raining, and you asked her to move a spoil heap that someone else cocked up in the first place, while you spent the day in the finds hut with your supervisors organising context sheets. At £9,000 a year tuition fees, we should be teaching archaeology students to excavate but we should be doing so whilst allowing more autonomy - and that includes allowing students with disabilities or medical problems or mental health issues to decide what they're capable of doing - in consultation with the director - not the supervisors.

And when directors think about possible 'red flags' of which to make students and other participants aware, they should be honest about physical barriers and potential hazards (and the reasonable adjustments that they can and cannot make), and they should also be honest about the reality of day-to-day life regarding potential lone working, likely stretches of inactivity and boredom, sex segregation and privacy, the toilet, bathroom and sleeping arrangements, the local fauna especially biting insects, and sensory issues such as noise at night and stuff like types of food available and the realities of queuing for food and showers.

I suppose for me it comes down to sharing - sharing honest information, sharing out tasks, sharing out labour and responsibilities, and sharing out that sense of pride and elation when the site yields up new knowledge and starts to tell its story. There's no room for elitism any more in the study of everyone's past - certainly not at the prices the diggers are paying. If we're all honest about the dig experiences we're offering, and we then share out those experiences equitably - so not necessarily equally, but fairly - then there should be digs out there where everyone can find their spot, and be set up not to fail but to succeed.

Many thanks to all the Twitter archaeologists for their valuable thoughts and ideas, and for relaying their experiences so effectively.

My main home page hub is here and I'm on Twitter @DrElScott

Excavation Challenges - Food, Fieldwork and Difference