Credit: Detail from cover of Excavations of the Roman Villa at Beadlam, Yorkshire by David S Neal for Yorks Archaeol Soc 1996

Back in the 1990s the then Inspector of Ancient Monuments David Sherlock decided to take me to visit the site of Beadlam Roman Villa in North Yorkshire, and asked me to write about it. I'd published a couple of bits of my PhD thesis on RB villas, and English Heritage had an interest in David Neal's write-up of the 1966-1978 Beadlam excavations. David Sherlock thought I might have some 'new light' to cast on these old stones.

Visiting Beadlam. Credit: Friends of Roman Aldborough. Better people than me.

Standing there in the field on that grey day, staring at lines of consolidated wall footings poking through grass, I wasn't really feeling it. But back in the Department Library in Newcastle, as I studied once again the plans and the information available, a lot of ideas did come quickly, and the inspiration was a blocked doorway. That changed everything. I've always been fascinated by Roman villas, what they were, what they meant, and how British people lived in them.

And so I did write a piece - but I don't think any part of it found its way into the English Heritage publication. The disk it was written on was put in a box, in a drawer, in a room. The box moved from Newcastle to Leicester to Portsmouth. I found it again last year - it's here - and think it's worth talking about in this Archaeology Blog; because I think it matters that there's more than one way to 'read' a villa site, and I do really think that these sites are important. Of course the study of the vast expanse of the rest of the Romano-British countryside is probably hugely more significant, but these Things Called Villas did exist, they would have changed the appearance of their landscapes and affected the lived realities of their inhabitants - and the nature and speed of their demise is probably telling us something very significant about the nature of the Romano-British economy.

In looking as Beadlam villa, I set myself some questions to answer. How unusual was a villa in this area of northern Britannia? What is the importance of the late burial? Are the contexts of the infant burials extraordinary or unusual? How significant is the villa plan in terms of J T Smith's influential 'Unity Theory'? How can we 'read' this villa within a Romano-British - as opposed to a classical - context?

Beadlam villa is in North Yorkshire (NK1 in the Gazetteer of Roman Villas in Britain, pp 149-153). Until I compiled the Gazetteer for my doctoral thesis, I'd been of the general impression that villas were quite rare in this part of the world. But in this one northern county there are dozens - over 40 - and the number known is rising as a consequence of developer-funded archaeology. Beadlam villa produced prehistoric evidence and Roman pottery dating from the first to the fourth centuries AD, with the villa buildings 'proper' appear to be third or fourth century foundations. This late date wasn't unusual either - other late villa foundations in the county include Holmes House, Drax and Wharram.

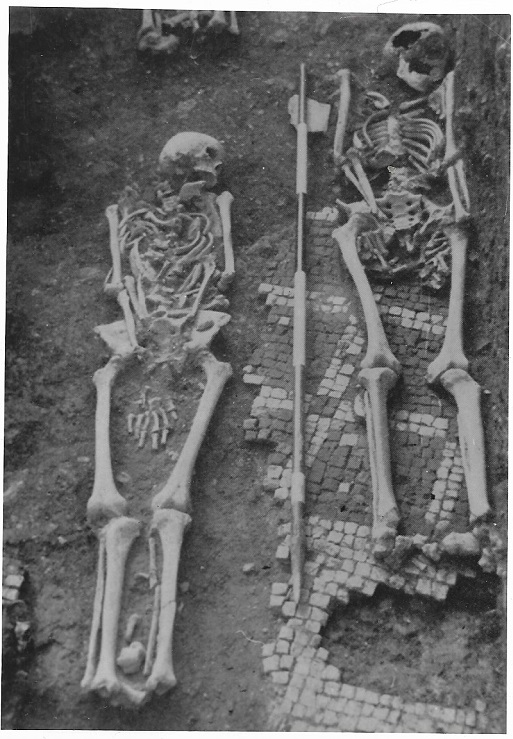

The disturbed skeleton of an adult female was excavated from among the rubble of Room 7 of the North Range, a room which had an opus signinum floor. It looks like this burial was either cut into the floor or laid onto a damaged floor and covered - and the former seems more likely. At the time I was researching villas for my PhD and looking at very late and sub-Roman burials like this on villa sites, there was a tendency for each separate example to be explained on a case-by-case basis basis, and so interpretations could be rather fanciful, such as people being suddenly attacked or vagrants crawling into ruins to die. I was looking at so many hundreds of villas that I thought I could see a pattern - a pattern of out-of-use villas or villas in their 'end days' being used as places of burial, especially those with probably visible apsidal buildings, including bath blocks. Also, burials were sometimes placed on 'special' floors, such as mosaics, tessellated pavements and opus signinum, and then covered up. This struck me as meaningful agency rather than a series of unfornuate events.

The usual parallel given for the Beadlam adult burial is Rockbourne in Hampshire, and evidence exists throughout the province - and is even more striking across the channel where the Christian connotations seem very clear. One need not go too far at all however to find parallels for Beadlam. At the Well villa in North Yorkshire a pavement was uncovered in 1876, over which were found infant bones, adult vertebra, roof slates and a hypocaust heating block. Were these burials acting out memories of a bygone era, in an age of Christian concerns? At Winterton villa, close to a main Roman route between York and Lincoln, inhumations were cut into the collapsed remains of the building, and were aligned with the building so its remains must have been visible. The Romano-British church may have collapsed along with the economic structure of Roman Britain, but the remains of villas, and particularly the colourful floors on which some later skeletons were laid, may well point to a meaningful religious practice. At Southwell, Norton Disney and many more villas, a pattern emerges.

Two infant burials were excavated at Beadlam. One infant appeared to be a premature delivery of 36-38 weeks and was buried outside one of the villa buildings. The second infant was about three years old, and was buried by a wall inside a villa building, with a complete pottery vessel placed at its head. Again, infant burials can be explained on a case-by-case basis, leading to various sensationalist interpretations, depending on one's current paradigm soup intake - the infanticide of illegitimate infants, or female infants, or disabled infants, or the unwanted male offspring of prostitutes.

There's no need though to see the two infant burials at Beadlam as unusual or to see them in isolation. I think it makes sense to ask the question: do these infant burials fit into a general context for infant burials in Romano-British villas in the fourth century, and if so, how? I've published a fair bit on how, from the early fourth century onward, it became increasing common for infants to be deliberately interred in and around the buildings, especially by or under walls, and in the agricultural processing areas of the site hubs. These could be single burials, or groups of burials. Some were buried with artefacts or with animals. Sometimes baby cemeteries can be identified - and they don't even have to be predominantly the result of infanticide, in a time of high infant mortality. The burials certainly have cultural meaning, and rather than telling us about 'lapsed' women they should be speaking to us perhaps of women's agency within site landscapes at a time of cultural change and eventual upheaval.

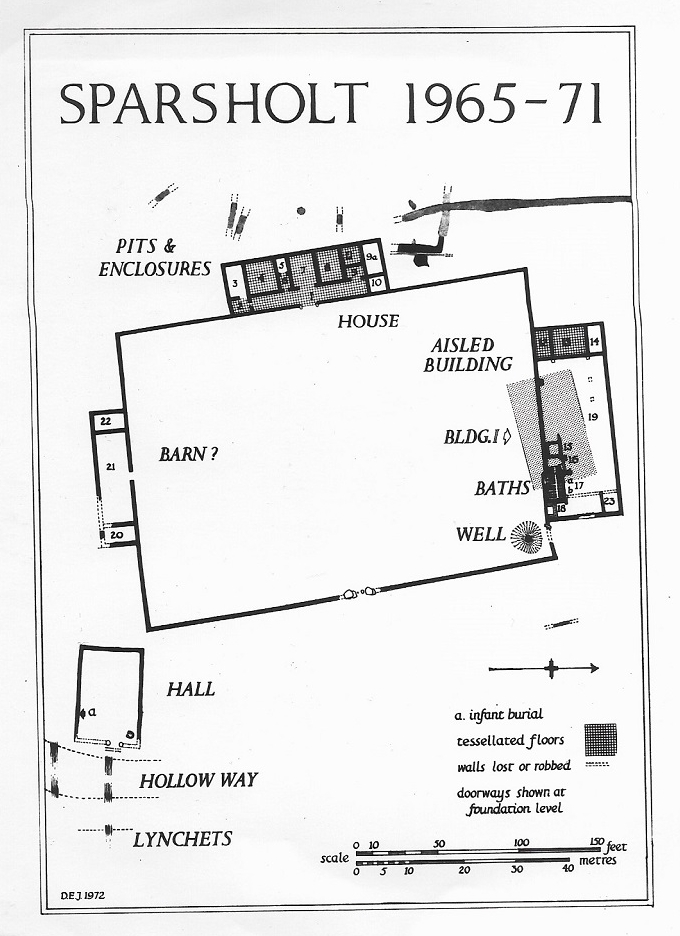

Sparsholt Roman Villa. Source: D E Johnston 1972 The Sparsholt Roman Villa, revised edition fig 1.

As for the site plan, Beadlam has been cited as an example of a villa conforming to 'Unit Theory'. J T Smith's theory holds that many villas in Roman Britain were owned and occupied by more than one household, and that such multiple proprietorship of villas is evident in villa plans where two or more houses, or building ranges, or suites of rooms, are present. Such dual ownership is allegedly the result of a pan-Celtic system of partible inheritance through north-west Europe.

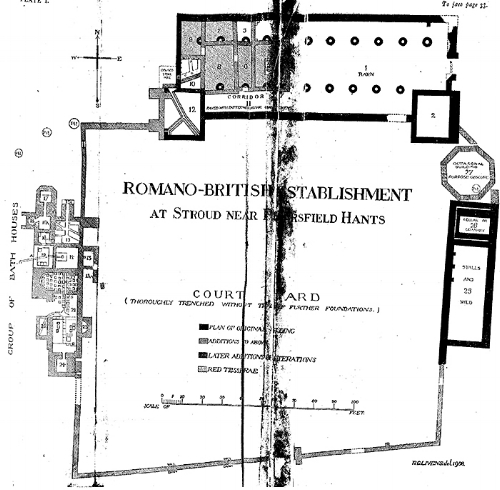

'Unity Theory' has had many critics, and I'm definitely one of them. My reasoning for why 'Unit Theory' doesn't work in Britain is because there's something uniquely British about many villas sites in the province that J T Smith didn't account for, and that's the frequency of villa sites where one building is a typical corridor villa house and the second building is nothing at all like that. Often, the second main building lies at right angles to the first, is a type of building I've only observed in Roman Britain and that can be labelled 'aisled farmhouses'. They were huge - 40 metres long in many cases - and bigger than the 'main' villa house (ie the one with a corridor and maybe fancy wing rooms, in the more 'Roman' style.) At sites like Stroud, the aisled farmhouse was the main house, dominating the layout of courtyard completely.

Stroud villa, near Petersfield, Hants

These farmhouses could have been the 'Home Farm' of a villa estate - they certainly seem to be the working focus of agricultural production and processing, possessing also living quarters of a decent standard. They tend to be late, and could indicate a nucleation of agricultural practices at the villa site hub that began in the third century and carried on and increased into the fourth, along with greater numbers of infant burials, animal burials and the appearance of malting driers for possible 'cash crop' purposes eg beer. (Interesting side-fact: beer was so important in the ancient world that one of the first names in recorded history belongs to government official Kushin responsible for a Sumerian beer brewery in 3100 BC.)

Inside the aisled farmhouses, evidence has been found to indicate they were used for human living alongside stalling animals, threshing and storage. Some of them had bath-suites - eg Sparholt in Hants - and mosaic floors so they were embracing the Roman whilst maintaining the traditional.

Who would live in a house like this?

If we think of these buildings as 'Home Farms', part of the site's hub, the answer may well be a younger generation of the villa-owning family, rather than a separate family altogether. Or how about, the actual family? The introduction of aisled farmhouses - large, imposing and all-purpose structures - usually at relatively close right-angles to the main villa house, from the late second century onward, speaks of economic and social changes on villa sites that culminate in a much more tightly controlled use of social space by the fourth century. Perhaps we're seeing a growing imperative to not only nucleate agricultural activities but to increase control over processing, exchange and sale, and inheritance. Perhaps these buildings - aisled farmhouses - describe the necessities of British farming, not classical aspirations.

But this was a money economy, and the Roman world was ever-present. The villas were consumers as well as producers of traded products such as ceramics, decorative products and charcoal. When that economy collapsed, the villas - or at least their spectacular archaeological visibility - went too, and rapidly.

But while the Roman economy functioned in Britain, did the strictures and requirements of that system - taxation, cash transactions, inflation, devaluation, enforced legalities of ownership, monetised supply chains - ever sit easily upon these British rural farming families? The mosaics of Yorkshire show on occasion an almost anti-classical rebel tone.

In the cases of the villas which seem to be dominated by these massive aisled farmhouses, where everything seemed to be going on, I've sometimes suspected that they functioned as the social and economic hearts of the site - and that the corridor house may well have acted as a kind of 'show house' for encounters with relative strangers from the outside.

Beadlam Roman Villa - mosaic

The corridor villa houses seemed to lean in towards 'Roman' so much, trying so hard - and yet at the same time they seem to pull back from it in their inner workings. The social configurations of space at Beadlam are like this.

(No aisled farmhouse or any 'outbuildings' are known at Beadlam, so they either didn't exist or more likely are yet to be found.)

The north range at Beadlam existed contemporaneously with the west range for perhaps only a short while. In the north range, people clearly moved around this building in quite a complex way. When a mosaic was laid down - a fairly standard looking early fourth century RB mosaic of the 'classical' canon - the doorway over the ditch was blocked up, so that access to the mosaic was carefully controlled. Access was gained via the following movements: through the main front door, straight ahead, turn right, into another room, turn right, and turn right again to cross into the mosaic room. These movements from the outside in order to get into the mosaic room and look upon the mosaic comprise four 'architectural steps' and gives the range a certain 'depth' - perhaps the pulling back of a private space into the heart of the habitus at a period of increasing economic and social pressure in times of growing turmoil and uncertainty.

This isn't a boring floor. Well it is a bit, but ... access to it maps how actual people actually moved, over 1600 years ago. The drawing in of formal space - in essence, making formal engagament with the outer world more private - seems to mirror the shrinking nature of an increasingly precarious Roman world.

So I've 'read' the site, but of course I don't know the place at all. I don't know and can't know, and my having physically stood there hardly matters. I know that people were born there and buried there. People paid their taxes there, paid a mosaic fitter there, gave birth there, grieved there, built walls and dug foundations there. In North Yorkshire, a family built a villa - but possibly lived only half a life within the hybrid walls and floors of this half-known space. Not knowing - it's not an archaeological crime. It's what makes it all worthwhile. You can't ever really measure it. It's quantum archaeology.

All references and sources are quoted in this longer paper on my website, and in the Gazetteer. The mosaics are in Hull Museum and Leeds Museum. Thanks to Simon Mays and David Sherlock of English Heritage. And to Richard Reece for 'Things Called Villas'.

![Beadlam Roman Villa [Plan adapted from Britannia i 1970 p.278 Fig.5]. Credit: http://roman-britain.co.uk/places/beadlam.htm](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57481c57f85082e7c413481f/1487516075298-X3T1L27QI884XOA9X2O5/image-asset.gif)