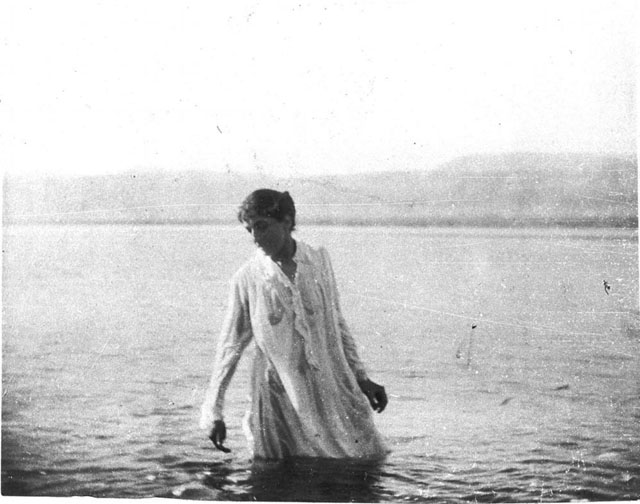

A particular photograph in Gertrude Bell's collection, taken in her very early years as a travel photographer, has drawn me back to it many times. It's an image of a European woman bathing in the Dead Sea in Palestine - then part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire - wearing full Victorian bathing gown and looking for all the world like she's in a state of rapture rather than in a harsh and unforgiving viscous lake of salt which burns like fire in your eyes and scorches even the slightest graze. It's not a typical formal Bell view of a building or a place - it's a thoughtful, intriguing composition.

I decided to research it and its context, curious as to what it might reveal about this point in Gertrude Bell's life and career, the subject of the photograph, and the landscape. If the archive notes are correct, Bell took this image ('possibly Mrs Nina Rosen') in June 1900. She was then 31, having been based in Jerusalem since December 1899. It's the work of Bell the photographer, and I've often thought about her origins and influences as a photographer. What and who inspired her? Was she any good at photography, and did she produce photographs as science as art, or both? What does her corpus of work say about her, and her life?

Her journals and letters say a lot - and I mean a lot - as she was a skilled wordsmith and gifted at crafting images for her intended audience, variously charming, familial, excitable, politic, sympathetic and melancholic. Her archive however is far from a straightforward narrative. There are almost too many words - her cacophony of stories entwined together, her literary orchestration part-crafted by her own self-imposed filters and the filters of historical context, is a very noisy world.

Bell tells tales of personal, political, archaeological and logistical experiences and necessities, very much through the constraints and traditions of late Victorian and Edwardian upper class letter and journal writing; and truth be told, I find her busy, exclamatory narratives strangely exhausting at times. In contrast, the photographs 'speak' more calmly, and they have always attracted me to Bell much more than her letters and diaries.

And her photographs are important documents. Many have now been published and discussed, but the examples from Jerusalem and the Dead Sea are pretty neglected, regarded I imagine as being among the less important views. The lack of interest in these photographs is an omission from the telling of the Bell story, I think, because these images and the friends who helped in their creation are part of Bell's beginning.

So in what ways are these early photographs of Jerusalem to the Dead Sea important?

1. These early photographs reflect what camera she was using and how portable it was for her

Bell was one of the generation of late Victorian and Edwardian photographers who benefited from the invention of the Kodak box camera and film roll in 1888 by American inventor George Eastman. This was a huge departure from earlier equipment that was extremely cumbersome and heavy, involving glass plate negatives and tripods, and which needed a fair bit of forethought to carry around. Bell did on occasion travel in the company of those who still preferred to use a plate camera, and have it carried as part of their horseback entourage. She wrote during her first travels in Jordan:

“Rode across the corn to Jelul ... stopped to photograph a camp of Christians from Madeba milking their sheep ... Mr B had his dragoman William and a man for his cameras. I had Tarif.”

So Bell was able to travel relatively lightly. In fact the cutlery and plates she rode with probably weighed more than her camera.

Within weeks of arriving in Jerusalem she was referring to her camera and needing rolls of film in her letters home:

“... I don’t want any clothes, but I do want the 2 doz rolls of films which I ordered the Photographic Association to send to Redcar and will you please have them sent to me [via the German Consulate]”

But Bell, who arrived in Jerusalem in 1899, was no lady tourist with a novelty Kodak. She was physically tough and adventurous and in the middle of her mountaineering years, with the fitness and the skills of an extreme sports athlete. She was also a scholar who understood the historicity of the monuments under her gaze. Thus, every one of her early photographs from Jerusalem and the surrounding area are illuminating.

2. They show Bell's growing competence in photographing landscapes and people - developing and practising both stylised and documentary approaches

She started off playing it safe, with views of the Old City, and in particular the gates of the Old City and the Haram Al-Sharif (Temple Mount).

I don't know if she was aiming to replicate views that she had previously seen taken by earlier photographers - eg the inside of Damascus Gate, shown here with the earlier Salzman image - but, at any rate, the first few weren't anything particularly special or invaluable. Carefully framed, competently taken, they were good photographs but not uniquely interesting - they were the photographs that any educated traveller might take.

Her competence grew, however, almost daily it seems. (A more detailed study of Bell's Jerusalem-based photographs of the Old City and the West Bank is here.)

And once she bought her own horse, everything changed.

3. They show how the Jerusalem and Dead Sea landscapes awakened her interest in the Middle east as a place in which to travel fairly independently

Map of the Levant during the Ottoman Empire prior to WW1 (Wiki Creative Commons)

It was when Bell started to get out and about on horseback that she started to experiment with different types of subject. Instead of focusing on 'safe' historic buildings, and posed portraits, she now began to incorporate people in naturalistic and artistic settings and to capture more esoteric and complex landscapes. In being able to leave the built environment for the desert landscape, she branched out creatively - leading to the Dead Sea photographs which so intrigue me.

She was still writing her twee, class-distinctive prose, but her eye was diverging from her pen. And importantly, she was not alone.

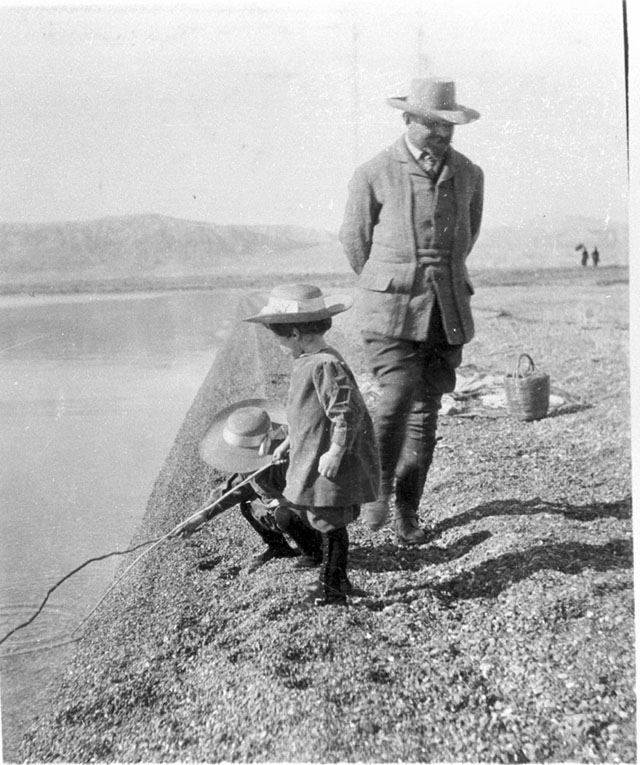

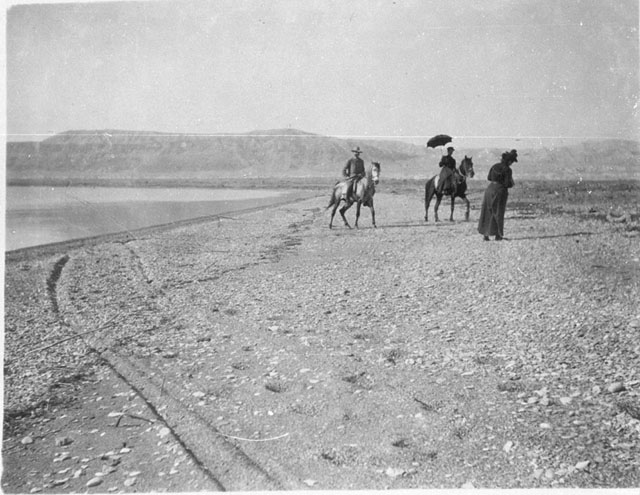

She rode down to the Dead Sea with the Rosens, a German consular family who had invited her to Jerusalem in January 1900, quite early on in her stay. During the journey, she took the photographs which are catalogued in the Bell archive as A130, A131 and A137. At this point she was still riding side-saddle, in the 'proper' way. She describes the Dead Sea as 'sticky' - she means going into the mineral-laden water itself, not the winter atmosphere - and the whole trip, the descriptions and the photographs have a feel of relative constraint and propriety.

But either later on in the day, or later on in the year, she photographed her friend bathing. (I think it's more likely that there was just the one trip with the bathing paraphernalia in January, and that the ''June' photographs are mis-labelled.)

That winter, Bell began to regularly ride out with the Rosens and Charlotte Roche, to see wonderful sites in the Jordan Valley, and to Jericho and Bethlehem. The Rosens had been in Jerusalem since 1898 - and Friedrich Rosen had been born there and spoke Arabic - and so they acted as knowledgeable guides as well as hosts, and were able to support Bell's learning Arabic. Bell stayed at the Jerusalem Hotel close to the cramped German Consulate in order that she might have two rooms in which to live and work, but spent a great deal of time with her hosts being tutored in the ways of the region.

Bell's letters and diaries from these months are full of descriptions of and exclamations (sometimes of disappointment) about buildings, landscapes and people - and within this there are many positive references to Nina and Charlotte. Bell was often far from complimentary about the people she met and spent time with - indeed her descriptions of the well-known figures she met from the Palestine Exploration Fund at this time are breathtakingly (and almost pointlessly) scathing - so this wasn't simple politeness towards the Rosen-Roche party. She genuinely valued the company of Nina, Friedrich and Charlotte - especially the latter if the number of references to her by Bell in her contemporary writings are significant.

Cricially, her hosts helped her to acclimatise to the region in a variety of ways, so that when she was finally ready to assemble her own small caravan to journey to further-flung places like Damascus, Baalbek and Beirut, she was ready, and came back to Jerusalem in one piece from her excursions in the middle of June 1900.

4. The Dead Sea photographs are a record of Bell's friendship with Nina Rosen and her older sister Charlotte Roche, and their influence on her in these formative months

The significance of the Rosens, and Nina Rosen's sister Charlotte Roche, is the scale of the influence that these accomplished and spirited people had on Bell. They may look like straight-laced Victorians in those first photographs, but they were adept at pushing boundaries, were cultured, and full of adventure. Gertrude Bell soon did two things. She gave up riding side-saddle to ride astride; and she branched out in her travels to visit places in Jordan, Syria and Lebanon without accompanying European chaperones - and furthermore she extended her travels without advance, explicit permission from her father.

According to Lady Bell, Nina Rosen had been known to the Bell family since childhood, being the daughter of Mr Roche of the Garden House, Cadogan Place, London. Gertrude Bell then met Nina and her German husband Friedrich whilst visiting Tehran in 1892 with her Aunt Mary Lascelles, where Uncle Sir Frank Lascelles was a British envoy. This was the period of the attempted engagement to Henry Cadogan, a man with modest prospects and, as it turned out, a great deal of gambling debt. The putative relationship was sunk not by any words from either Aunt or Uncle Lascelles, nor from any interventions by the Rosens, but by the refusal of her father and step-mother to give approval to such an idea. Whilst Gertrude Bell accepted her parents' word on the matter she was significantly affected by the experience, and from then on it seems she saw the Middle East as a backdrop to having (or being permitted to perform) heightened emotions and intensity of feeling - it's clear through her prose and poetic translations of this time and later. This was a controlled chanelling of her emotions, but she obviously felt them.

In or around 1898 the Rosens were relocated to the German consulate in Jerusalem and invited Bell to spend the Christmas season of 1899. Bell accepted the Rosens' invitation, and began her life-changing trip in mid-December that year. She'd liked them in Tehran, Nina a gifted musician and Friedrich a talented Arabist.

She bought her own horse and saddle almost immediately, and the trip down to the Dead Sea in the new year with the Rosens was a side-saddle affair. But by March, she'd observed Nina riding astride using a 'masculine' or 'man's' saddle, and Bell herself took to riding astride her horse in April 1900. Bell also frequently travelled out on horseback with Charlotte - like herself dynamic, vibrant and unmarried - and who, according to the memoirs of a surviving relative of the Roche family, Henry Roche, was notably cultured and 'studied at the Slade School of Art and was an accomplished photographer'.

“Glorious hot day. Went out photographing with Charlotte and the boys all round the walls [of the Old City]”

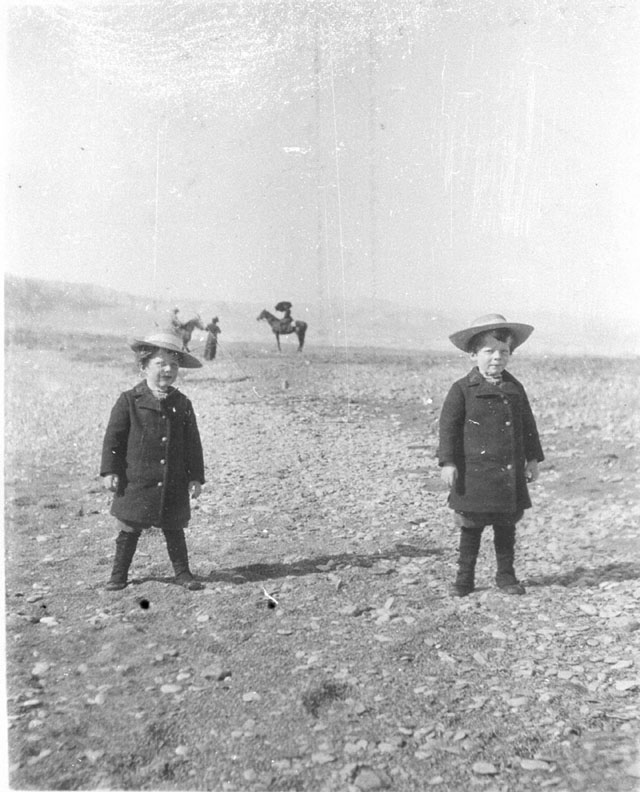

The boys were Nina and Friedrich's twins, Oscar and Georg, of who Bell was fond, and of whom she took many photographs during her stay. She found a special friend and photographic companion in Charlotte, mentioning her frequently in her letters of December 1899 and January 1900.

“On Friday Dr R. Charlotte and I went to the Haram - officially this time - and I photographed while there was sun (which was not long)”

Over these first two months in Jerusalem, it seems extremely unlikely that Bell would not have learned a great deal about photography and composition from Charlotte Roche. Indeed it was after going out and about photographing with Charlotte that Gertrude Bell wrote home to check on the dispatch of her new rolls of films.

And this - this sense of throwing off convention and re-framing her own needs, this sense of learning, and the seeking and finding of freedom in a foreign land, and finally noticing and observing the dichotomous rigidity of the European position in the Middle East - this is what I see in the photographs of Bell's trip(s) to the Dead Sea (see especially A556, A557 and A561). Bell had always had a veneer of confidence, but now she was developing the skills to go with it.

The bathing photograph of Nina certainly seems a signifier perhaps of increased friendship, confidence and photographic skill. And whether they're from one trip or two, the Dead Sea images also tie in with Bell's increasing keenness to take posed photographs of people, and not just capture views of places.

So close did she grow to Charlotte, that she wrote on her return to Jerusalem from Beirut that they would now be staying in the same hotel together until Bell's return to England later that month.

“Charlotte and I both at Kamnitz’s for good.”

And Bell knew she would most definitely return to the Middle East.

5. The Dead Sea photographs are an echo of her growing streak of melancholic romanticism, which was to mark her life with highs and deep lows

Bell was intensely practical when it mattered, but she was not without a streak of strangely destructive romanticism. I've referred previously Bell's possible lack of judgement when it came to the men she desired to marry (and see also my piece The Death of Gertrude Bell).

She certainly wasn't short of suitors. She simply tired of Billy Lascelles and Bertie Crackenthorpe, who weren't on her level (as she saw it). The ones she actually wanted to marry, though, were a whole different matter. Henry Cadogan appears to have been a gambler and something of a 'future-faker', making promises to her he couldn't keep and which were patently unrealistic. Her other two later loves, Dick Doughty-Wylie and Ken Cornwallis, were both already married - unavailable, and unobtainable without the most incredible drama and upset being created affecting many parties.

The photograph of Nina in the water, verging on the style of a pre-Raphaelite tragic heroine, taken after Cadogan but before Doughty-Wylie - is this Bell looking into a mirror, reflecting her own feelings of melancholy and struggles with attachment? Bell's letters home show her often as a bit of a 'people-pleaser'. Her parents' approval and her father's love mattered to her a great deal, seemingly above all else; yet she was remarkably often very far away from the home she craved, being 'useful' - and lonely.

6. Her photographs are also part of an archive of Victorian images which pre-date the development and deterioration of the Dead Sea landscape and environment

Bell's photographs are an important part of the pictorial archive for this region, yet have not been included in the main works for the history of Palestine / Israel. (I was surprised when I was talking to British and Israeli scholars in Jerusalem in 1990, as part of the Gertrude Bell Photographic Archive Project, how little interest there was in her.)

The geographic beauty and the therapeutic qualities of the Dead Sea are mentioned in many ancient texts and a modern source of revenue for both Israel and Jordan. The image of the woman which Bell captured in 1900 is part of the historical narrative of belief in the Dead Sea's restorative powers.

I was out of that sticky, acid water the minute the photograph was taken ...

I first visited the Dead Sea and Masada in 1984, and even back in the 1980 and 1990s concerns were being raised about the receding waterline caused by the mining of salts and other minerals from the sea and the extraction of water from the River Jordan, the Dead Sea's only feeder river, particularly from the Israeli side.

This, along with the development of tourist and transport infrastructure, has led to an environmental crisis today affecting a complex ecosystem of Bedouin people, wildlife, geology, archaeology and settlements - sink holes and increased evaporation being just part of the problem.

Victorian photographs such as Bell's - and they really ought to be better known amongst British and Israeli scholars - are part of the testimony to just how much and quickly things have changed in the Dead Sea area since 1900, as well as being historical documents in their own right.

And so ...

Gertrude Bell's letters and journals were a performance for the benefit of her family and her class, and her letters and journals were what her family members concentrated on publishing after her death. Her photographs, however, were Bell's performance to herself - still in many ways carefully constructed and contained, but nevertheless on occasion more spontaneous, genuine, revealing and personal, and perhaps a medium through which Bell can be experienced with far less background chatter. Through her photographs Gertrude Bell emerges possessing the same authentic yet fragile eloquence as the landscapes and people she temporarily captured through the lens of her camera. And we owe thanks to her friend and mentor Charlotte Roche for that.

Sources: The Gertrude Bell Archive, Newcastle University; Unpublished report (kindly provided by Gertrude Bell Archive) by Jonathan Godfrey, July 1988 Gertrude Bell, Photographer: a preliminary reports into her cameras and methods, Newcastle upon Tyne; Unpublished lecture from late 1980s by Dr Jeremy Johns, Oxford University; Catalogue of the Gertrude Bell Photographic Archive 1985, by Stephen Hill, Lynn Ritchie and Barbara Hathaway, Dept of Archaeology, Newcastle University; Georgina Howell 2006 Daughter of the Desert: the remarkable life of Gertrude Bell, MacMillan; Shirley Eber & Kevin O'Sullivan 1989 edition The Rough Guide to Israel and the Occupied Territories, Harrap-Columbus, London; Janet Wallach 1996 Desert Queen, the Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell: Adventurer, Advisor to kings, Ally of Lawrence of Arabia, Phoenix; Henry Roche's epilogue of reminiscences (p 338) in Mark Kroll 2014 Ignaz Moscheles and the Changing World of Musical Europe, the Boydell Press; http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Gertrude_Bell.

Edit (2nd Feb 2018): to include detail about Nina Roche's childhood home at Cadogan Place from http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Gertrude_Bell, drawing on Lady Bell's The Letters of Gertrude Bell (1927).